Do you know what your perfect day would be? I’m not talking about like Ferris Bueller’s Day Off or the best Christmas ever or getting invited to the ultra-hot-people-only orgy. I mean what would your perfect, random, workday, Wednesday be like? I imagine for most of us it would be pretty simple, something like: wake up rested, have a nice breakfast, nothing weird happens at work, maybe lunch in the park or some shit, and have a little time to relax before going to bed and starting it all over again the next day. For better or for worse, days like that *should* make up the majority of our lives. And yet, if I’m speaking for myself, I don’t give myself the gift of perfect days nearly often enough. Far too often I wake up exhausted or spend too much time about stressing going to the gym or put off doing work and chores and preparing food. It keeps me hanging on. I should change that, yeah?

Hirayama (Shall We Dance? and 13 Assassins‘ Koji Yakusho) is on the far other end of the daily structure spectrum from me. This middle-aged public toilet cleaner has got his routine down to a science and adheres to it rigorously. We see that every day begins the same; he wakes up, makes his bed, waters his plants, brushes his teeth, smiles at the morning sky, buys a can of coffee from the vending machine, gets in his car, takes a sip and puts in a classic rock tape, and drives to his job in upscale Shibuya. He works diligently and silently, with an attention to detail that seems absurd but maybe it’s just Japanese (he uses a mirror to make sure he’s cleaning angles he can’t see under urinals, for example). He enjoys lunch at a shrine in the woods where he photographs the trees and notices a woman who also eats lunch there seems to notice him back, but neither say anything. After work he goes to a bathhouse and then to a bar where he has a standing order waiting for him. At home, he ends the day reading the likes of William Faulkner, Aya Koda, and Patricia Highsmith.

I’m able to recount this routine of the dome because Perfect Days shows it to us many, many times in its two hours. As you might expect, the movie is about the subtle disruptions Hirayama deals with in this approximately two-week slice of his life. Disruptions such as his younger coworker Takashi’s (Tokio Emoto) preoccupation with trying to woo an even younger bartender named Aya (Aoi Yamada), which results in Hirayama giving them a ride. Or the time when Hirayama’s niece Niko (Arisa Nakano) suddenly appears out of the blue and asks to stay with him and shadow him at work. Or even just how Hirayama spends his one day off a week (don’t worry, he’s got a schedule for that too). These diversions give us some insight into Hirayama’s past, but if you’re looking for a reckoning, this is not the movie for you. Paterson is an emotional roller coaster compared to Perfect Days.

But if you did want to compare Perfect Days to other films, I’m sure director Wim Wenders would be happy to point you in the direction of Yasujiro Ozu. After all, Hirayama’s name is deliberately borrowed from An Autumn Afternoon, Ozu’s last film (and one Colin hasn’t gotten to yet). This is a peaceful, contemplative movie. More than that, Perfect Days is a Rorschach test for how you feel about solitude. Hirayama spends a lot of time in public spaces — shrines, parks, bars, the bathhouse — but he’s alone and he keeps to himself. He laughs at fellow bar patrons reacting to a televised baseball game and makes polite conversation with the friendly proprietor (Sayuri Ishikawa) of his favorite restaurant, but mostly he’s an observer instead of a participant in social life. You might view that as a tragedy, that’s totally reasonable. I view it as contentment. I think whatever tragedy Hirayama dealt with is in his past and he found his own version of happiness.

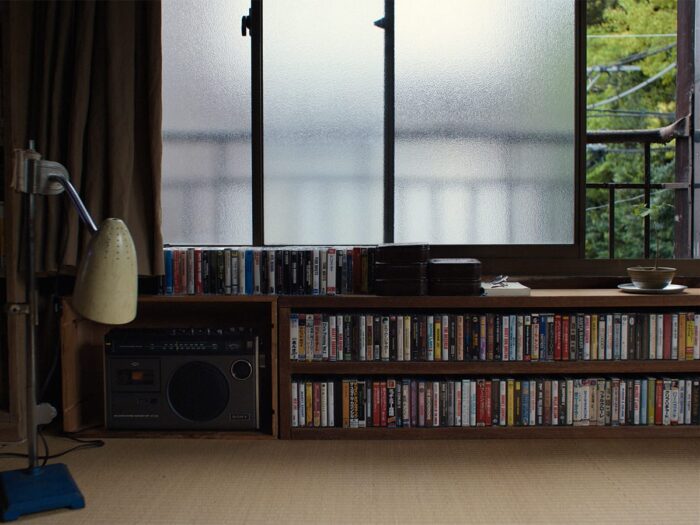

Another vibe check you might need to pass is how into a simple lifestyle are you? This goes a bit further than Cottagecore, Hirayama has no screens in his home. He takes pictures with an Olympus camera from the Nineties and has to get the film developed on his days off. His two main forms of entertainment are listening to Seventies music on cassettes and reading books he buys from the discount rack at the used books store. He does not appear to have a smart phone. When his niece asks him if an album they’re listening to is on Spotify, he tells her he hasn’t been to that store. So that’s where we’re at. There are a bunch of ways to read into this, he could be a Luddite or deliberately old school or a minimalist or just plain poor. I think it’s the movie telling us that this is someone who yearns for the past. Is that a rejection of modernity or a trauma response or actually healthy nostalgia? Who can say? But it’s fun to think about.

Hirayama works for “The Tokyo Toilet” in the movie, and that’s a real-life urban redevelopment project that hired architects to build modern, upscale public restrooms in common areas around Shibuya as a way to revitalize the spaces they exist in. The project was meant to be a big part of the tourist experience of the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games, but when the pandemic delayed them, the founder, Koji Yanai of Uniqlo, decided to invite world-renowned filmmakers like Quentin Tarantino, Martin Scorsese, and Steven Spielberg to make a documentary about the project and its effect on the community. One of the directors who came out was Wim Wenders, who talked them up to a series of shorts films and then ultimately a full-length feature. It seems like that really worked out for them, as Perfect Days won Koji Yakusho the Best Actor Award at Cannes and was nominated for Best International Feature at the Oscars this year. And yes, public interest in the toilets has surged, or should I say overflowed?

Hell yes to ending Criterion Month on a toilet joke