51st Academy Awards (1979)

Nominations: 6

Wins: 2

Turns out I didn’t plan this Oscars Fortnight terribly well. I was planning on reviewing 1978’s Coming Home today, but didn’t realize until I sat down to watch it that it’s currently not on streaming (whoops). Then, after scrambling to find another Best Picture nominee from the same year (since I wanted to keep my pattern of reviewing movies 10 years apart), I found that my second choice, An Unmarried Woman, also isn’t currently on streaming. This is a bit of a nutshell commentary on the less-than-ideal state of streaming classic movies currently, and also happens to be how I landed on Midnight Express, a film I’d always meant to get around to seeing, even if it lived up to its reputation as being a bit of a rough watch.

One thing Midnight Express has in common with Coming Home is that it also has the quality of being one of those ’70s movies that are “about what’s going on, man”. This is the true story of Billy Hayes, who just a year earlier published his memoir about his experiences enduring the conditions of living in a Turkish prison in the early ’70s. The film begins when college-age Billy (played by Brad Davis) is vacationing in Istanbul and is about to board a plane home to the U.S., though the one hitch is that he has strapped himself with about a dozen or so bricks of hashish that he’s trying to smuggle. However, Billy and his girlfriend are stopped by the police and asked to answer for his crime, which he says he was just doing for a little cash for a taxi driver he’d met.

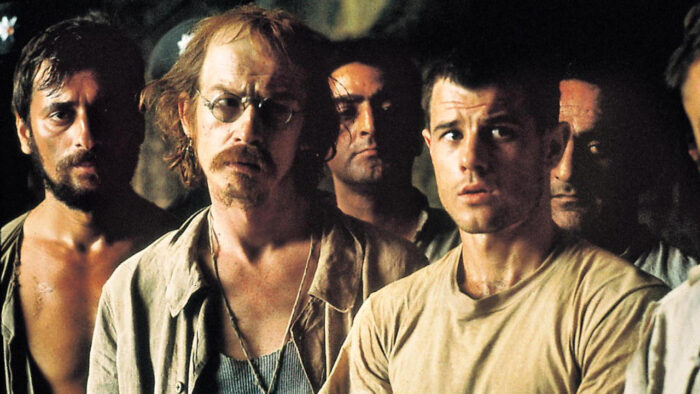

The authorities aren’t able to track down the taxi driver and Billy unfortunately has a hard time finding an honest lawyer in Turkey to defend him. He ends up getting a lighter prison sentence of four years for the drug possession while the smuggling charges are dropped. While in prison, Billy gets accustomed to the brutal nature of this particular type of confinement, while he also meets a few other English speakers (who include Randy Quaid and John Hurt) who he forms a kind of posse with. After Billy’s first three years, Billy finds that his sentence has been overturned and he’s now been slapped with a 30 year smuggling sentence. From here, we see Billy and his pals hatch a plan to escape, while his treatment in the prison becomes more and more brutal.

The two Oscars that Midnight Express received were for Best Adapted Screenplay (for a script by Oliver Stone) and Best Original Score (for Giorgio Moroder). I feel like both of these wins are rare cases where the Oscars were ahead of the curve in recognizing talent, as this was the first studio film Oliver Stone had worked on and Moroder’s first crack at scoring a film. Both of their styles would become more and more prominent in the ensuing decade, as synth-driven soundtracks became the norm and Stone’s sensational brand of boomer-centric period pieces became a part of several Oscar cycles.

It’s actually pretty remarkable that Midnight Express feels so much like an Oliver Stone movie, even though the film was directed by British prestige journeyman Alan Parker and adapted from Hayes’ book. Yet, somehow Stone’s heightened political style shines through in very exciting ways, as the ways in which Billy is treated is a little terrifying and also filled with rage against an unjust system. That said, like a lot of Stone’s directorial efforts, nuance is not exactly his strong suit and the film never really gets that deep into the specifics of why the prison conditions in Turkey are so bad. It also doesn’t get that deep into absurdity of The War on Drugs, but it would be hard to expect considering the film was made right in the thick of it.

So what you get in the end is a movie that plays up the thrills of a good prison drama — the bonds that form in confinement, the helplessness the inmates feel, the thrill of escape — but with the post-’60s feeling that the rules of law and order around the world had irreperably changed. As much as I like this more contemporary incarnation of the prison drama, the film certainly has its share of flaws, such as its relentlessly unflattering depiction of Turkish people or the sometimes shaky performance of Brad Davis. Still, it’s a fascinating look at the ways in which Hollywood studio films were changing right before the dawn of the ’80s and a bracing reminder why people always talk about avoiding getting stuck in a Turkish prison.