I used to love Mumblecore films. The idea that you could take a few friends and film an improvised drama or comedy on consumer-grade cameras was inspiring to my younger self. Sean Baker is not part of the mumblecore movement, but he taps into the same part of my brain that loves mumblecore. Baker’s films have the same lo-fi, improvised feel as a mumblecore film. He also uses numerous non-professional actors, often in major roles, but there’s a key difference that not only separates Baker from that movement but also elevates his work above most of those films.

A plot. Even if it’s subtle, there is always a force in Baker’s films that compels his characters through the events—no matter how mundane they may seem. In Take Out, that driving force is survival. Ming Ding (Charles Jang) is an undocumented Chinese delivery man working for a family-run Chinese restaurant in New York City. Smuggled into America illegally, Ming Ding is confronted by his smugglers with an ultimatum: he must pay them $800 by the end of the day for their smuggling services, or his debt will double. This means Ming Ding has to collect whatever he can from tips and loans over a single day, all while enduring a seemingly never-ending torrential downpour.

Before I go any further, it’s important to note that this film was written and directed by Sean Baker, along with his colleague and long-term producer, Shih-Ching Tsou. This is significant because, despite its U.S. setting, most of the film is in Mandarin, which is a unique experience for a generic American white guy like me. It’s easy to forget how much harder the “American Dream” is for immigrants. As you can imagine, Ming Ding encounters a wide array of personalities and viewpoints, some bad, some worse, but he endures it all to build a better life.

The film is shot much like a mumblecore film, on digital video with no shortage of zooms. The handheld camera gives the film a docudrama feel and adds to its authenticity. I respect that Take Out never tries to build to anything too unbelievable in its climax just because it’s a movie. For example, Ming Ding doesn’t decide to rob a bank or steal from mobsters or anything like that. There is a climax, but it’s the kind of interaction you can imagine happens in NYC every night. The streets are rough, dude.

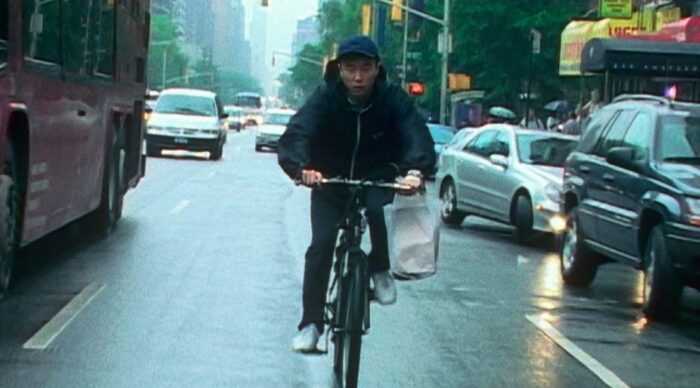

The streets are wet too. I forgot to mention that Ming Ding rides a bike, and almost every outdoor shot is in the pouring rain. Take Out employs every touch to highlight that Ming Ding is not having a good day. That being said, his co-workers and friends are joyous characters. They show why families immigrate to the States in the first place: to work, live, and laugh together while building something special, even if it’s just a dime-a-dozen Chinese restaurant. There’s not much levity outside the strength of Ming Ding’s community, but man, what strength they bring to make this film feel warm and alive when it needs it the most.

Before Take Out, I hadn’t explored Baker’s pre-Tangerine body of work, but I should. There’s a magic in finding the right actors, no matter how experienced, to tell a specific story. Not just a story—an experience. An experience that’s overlooked by most other films. Films that broaden horizons but also feel relatable, even if they’re about people who couldn’t be more different than you and me. Personal stories, but with a driving plot. Unlike Mumblecore. Don’ worry Mumblecore, I still love ya.